Valerie Collymore finds artistic inspiration from her unique childhood in France

By Jack Hamann

At the age of 9, Valerie Harmon was the only African-American—and, in fact, the only American—at her first day of school at Lycée de Jeunes Filles in Nice, France. She didn’t know a soul, and she didn’t speak French.

Her teacher, Mme. Hémard, began the semester’s first lesson speaking only in French. Scanning the room, she noticed Valerie, her head bowed as she furtively paged through a small French-English dictionary beneath her desk.

Valerie should have been terrified, but she wasn’t.

“All of a sudden, this hand dived down and pulled up my hand,” she recalls. “At first, she had a severe look. She had no idea [that I couldn’t] understand a word she’d been saying, and she kept speaking French.”

Any other 9-year-old might have melted—but not young Valerie. “I remember thinking, ‘This is hysterical. It isn’t something frightening. It’s a challenge.’ That’s just how I’m wired.”

Now 59 and living in Bellevue, Washington, Valerie (now Valerie Collymore) remains differently wired from others. An accomplished full-time artist, she is a former pediatrician, a former athlete, the mother of two high-achieving young women, and the daughter of a unique bon vivant.

This story begins with that one-of-a-kind mother. In 1965, Sylvia Harmon was a 39-year-old widowed nurse and the mother of 9-year-old Valerie and 12-year-old David. Good jobs and white families were fleeing her Camden, New Jersey, neighborhood. Vacations often meant visiting restaurants and motels that refused service because of the color of her family’s skin. She wrote increasingly radical poetry about racial politics and was arrested after refusing to leave a segregated hat shop. “She was horrified by what was happening in America,” says Collymore.

After a series of sleepless, chain-smoking nights, Harmon shocked friends and siblings by announcing plans for a European Grand Tour with her kids. Despite pleas from her six brothers, Harmon and her children set sail for Amsterdam. For several months, they camped in a Volkswagen van while seeing the sights of Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy. Arriving in Nice, Harmon fell in love with the French Riviera and decided to stay. Weeks later, Valerie found herself in Hémard’s classroom.

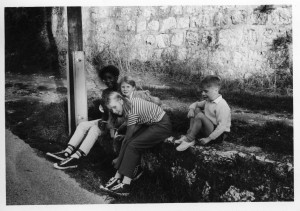

Valerie Collymore as a youngster with her friend Jane Lepage and Jane’s younger siblings.

Once Hémard realized that her new student couldn’t speak French, she took a liking to her, as did most of the girls in the class. They helped her learn the language, and she soon found success in a range of subjects. “I think it was a world-class education at that time, including art.” Collymore says. “I still have a folder from elementary school. They were doing a lot of color theory and values, and we were, like, 10 and 11. I was the kid that was always drawing.”

As her peers back in America came of age in the tumultuous ’60s, Collymore experienced an idyllic childhood in an alternate universe. “We had lots of freedom,” she says. “My best friend Jane and I regularly explored neighboring villages. I was immersed in this amazing culture with so much art. I walked past the Matisse Museum every day on the way to school. I studied concert piano across the street from the Chagall Museum.”

Every school holiday, Harmon packed the kids into the car and drove to Rome, Athens, Paris, and beyond. “In her mind, that was the best education,” says Collymore.

The American military had a big presence in Europe, including a popular USO in Villefranche-sur-Mer, a picturesque port adjacent to Nice. While visiting there, Harmon met a general’s wife who was interested in plein air painting, and Harmon volunteered to drive her to scenic locations. Appreciating Harmon’s eye and education, the general’s wife insisted that they learn to paint together. Combining talent with passion, Harmon became an insatiable student, taking classes whenever she could. She learned acrylics, oils, aquatints, and metallic prints, and she ultimately excelled in watercolors. Her landscapes were eventually exhibited in Monte Carlo and elsewhere.

“As she became an artist, my mother started seeing color,” says Collymore. On long drives through the French countryside, Harmon would sing songs designed to draw her daughter’s attention to the subtle hues that she noticed. Lavender clouds. Turquoise ponds. “The French Riviera has brilliant light—colors like nowhere else in the world—and intensity of color that’s just unparalleled,” Collymore says.

When she entered high school, Collymore displayed a talent of her own: athleticism. Her track-team sprint times were so fast that she was offered a chance to compete for the French National Team, on the condition that she become a naturalized French citizen. But her mother had other ideas. All along, she was determined that both her children would return to America and enroll in top colleges. Despite Valerie’s athletic talents and affinity for art, Harmon wanted her daughter to study for a degree in pre-med.

As the widow of a veteran, Harmon paid most of her bills with Social Security and Veterans Affairs (then Veterans Administration) benefits. Her late husband had started a college fund for his children, money that Harmon had instead spent exposing her children to art and history during those trips throughout Europe. But her time around military brass and other well-connected American expatriates paid off. Many had attended prestigious colleges and were willing to open doors to contacts at their alma maters, especially those looking for talented applicants who would also help those schools become more diverse.

Collymore was accepted at Radcliffe College, but her mother insisted on Brown University, which offered an experimental seven-year medical program. Providence, Rhode Island, however, proved too provincial for Collymore. She says that Brown’s white professors had low, racially skewed expectations of her and that fellow black students ostracized her for her unusual upbringing. “I didn’t even know who Stevie Wonder was,” she admits. Fed up, she transferred to Columbia, where she flourished in the bright lights of New York.

While in med school, she met—and eventually married—fellow student Victor Collymore. After graduation, the two young doctors moved west, eventually landing in the Seattle area, where they raised two daughters. Both girls excelled in school, became collegiate volleyball All-Americans, and spent time competing on the U.S. National Volleyball Team. Each gravitated to her own corner of the art world—Jane to music and Jill to filmmaking. For 30 years, Collymore put aside her own art.

By 2008, both daughters had graduated from college. Now an empty-nester and no longer practicing medicine, Collymore reluctantly accepted a good friend’s invitation to a Seattle Women’s University Club art class. “I thought, ‘Valerie, you’re a grown-up. A couple of classes aren’t going to kill you.’”

But sitting in front of a blank canvas was intimidating—troubling, even. At the first class, she couldn’t even pick up a brush. “Something was confusing. There was some unresolved emotion around painting.” A second class produced more anxiety. At a third session, however, her inhibition melted. “When the brush touched the canvas, something happened, which scared me. I thought, ‘I’m a physician, not an artist; this is ridiculous.’”

For the next year and a half, she felt haunted “by a huge magnetic attraction that this was something I was supposed to do.” She continued taking classes. Paintings poured out. Patrons and admirers purchased several of them. She sought out—and studied under—master artists. By 2010, she decided she was ready to call herself a full-time artist.

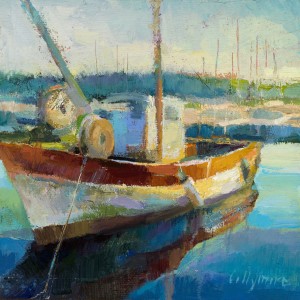

Collymore is an impressionist; her medium is oil. Although her works include still lifes, her focus is landscapes. Most of her paintings are of the French countryside, particularly the Riviera and Provence. “The places I paint today … were places I walked,” she says. “These were places [where] I was a happy child. These are places we went to with my mom. These are all places that are very meaningful.”

Every year, she spends as much time as she can afford—usually a couple of weeks—in France. On some trips, she visits sites where Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Renoir painted. She heads out alone in the early morning, experiencing and absorbing color and light. Because she can’t yet spend enough time to paint an entire exhibition while visiting, she takes thousands of photographs. “They are a reference, but photos lie,” she admits. “They never capture exactly what is there. So I really soak it up. I do a lot of looking, sitting in the fields, experiencing. I want to be able to remember what it felt like—what the colors looked like.”

There is never enough time. Collymore’s childhood friend Jane still lives there, and each visit includes a whirlwind of meals, memories, and long walks with old friends, including a former classmate or two from Hémard’s schoolroom. A favorite novelist, Marcel Pagnol, penned a line that she holds dear: “France is the homeland of my youth.” And art now offers the most meaningful way to embrace those happy memories.

Collymore’s unique mother, who had exposed her children to the world of art at an early age, repatriated from France to remain close to her children. At Collymore’s urging, Harmon remarried at 79. Six months later, she died of heart failure—peacefully, just as she would have wanted, says Collymore.

For more samples of Collymore’s work and a schedule of her exhibitions, please visit valeriecollymore.com.

Nagalingum MOOTHEE

9 September

Great painting and memorable site paintings