Find out what sets illustrators apart from fine artists, and what brings them together.

by Toni Fitzgerald

When Jon Krause was in college, he took a painting class. One day, his professor asked him what he wanted to do after he graduated. Krause told her he wanted to be an illustrator.

“She shook her head and said, ‘I could see more for you than that,’” remembers Krause, who has gone on to become a successful illustrator. “I think in some circles, [illustrating] is still looked down on.”

Krause’s college experience is a microcosm of the debate that’s long simmered in the art world: Is there a fine art to illustration? Though many illustrators have long since answered that question for themselves with a resounding yes, others may disagree.

“I’m not sure the discussion will ever be over, and I’m not sure it focuses on the same issues for all participants,” says Susan LeVan, illustration chair at the Art Institute of Boston at Lesley University. “For me, being an illustrator allows me the freedom to do the work I want regardless of the current critical atmosphere or politics of the fine-art world. But I could be a fine artist with the same attitude.”

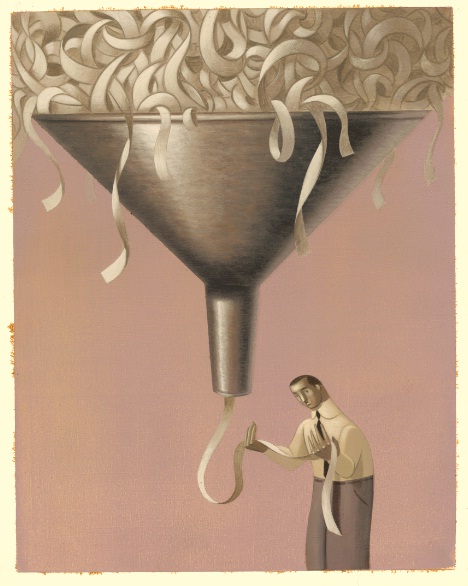

In the simplest terms, what separates illustration from fine art is a paycheck. Illustrators are paid to bring an idea to life, whether it’s the science behind the human brain or a child’s fairy tale—all while meeting a deadline. An artist, on the other hand, may spend a lifetime chasing a personal muse and never see a cent for it.

Krause, who lives in Philadelphia, has worked for some of the best-known book publishers, magazines and newspapers in the country. He says the difference between fine art and illustration is that fine art requires you to please only one person: yourself. With illustration, you must answer to many people. “As an illustrator, you’re being hired to do a job, you have to apply your skills to a piece of text and you have to please a lot of people,” he says. “Ultimately, if you do all that, you can get hired again. Every job is a job interview.”

The line between fine art and illustration is blurrier than the art world acknowledged just a few decades ago. For example, a 1990 Museum of Modern Art show entitled “High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture,” demonstrated how often the two worlds overlap and helped strengthen the case for illustration as fine art, says LeVan. “Some illustrators make a living creating personal work that’s exhibited at major museums and sold through dealers [and college illustration programs that offer gallery/fine art as a concentration],” she says. “Likewise, fine artists have produced commissioned work throughout history.”

Most illustrators say there’s definitely a fine art to illustration. “I don’t see a difference between the two at all,” says Angie Wang, a Los Angeles-based illustrator. “As a kid, I looked at an illustration as something that existed on its own. It is paired with an article. That’s its commercial purpose, but on its own it could have merit.”

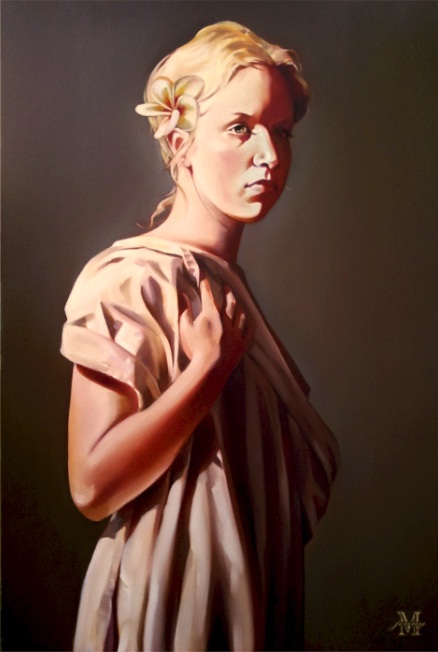

Jenny Medved, an illustrator from Sarasota, Fla., agrees that fine art and illustration share many qualities. “A strong work of art, regardless of its intention, needs to have the same elements: successful lighting, form, color and composition,” she says.

Of course, each person ultimately finds the answer to the illustration-versus-fine art debate in that person’s definition of “art,” and that definition is a personal one. If art, as one popular interpretation goes, is about communicating a message, then illustration is fine art. “I have to toe the line of staying true to myself and my artistic integrity while also answering the call for that specific assignment,” says Krause.

If, as others suggest, art is about asking questions and not just answering them, as illustrators often do, then illustration may not fit the definition of fine art. Although Krause notes that he consciously chose his profession so that he could satisfy his artistic leanings “and pay the bills and eat,” there’s no denying that some artists see illustration as selling out. “Historically, the fine-art world has wanted to separate itself from what it sees as the taint of commercialism,” LeVan says.

“I guess I realize why they want to make the distinction [between fine art and illustration], but that’s not really the case with me,” Wang says. “I kind of think it’s snobby.”

People are likely to debate illustration’s place in the fine-art world as long as there are books to be illustrated and cartoons to be drawn. That fact, at least, is one both sides can agree on. “I think this is an age-old question. I believe it will always be discussed because there is such a fine line between the two,” Medved says.

Mary Azarian art lesson for kids - Liberty Hill House

14 December

[…] illustrators fine artists? There is a lot of debate about this issue in the art world, basically centered on the question of whether artists’ choices should […]

URSULA JULVE

12 April

i did for many years was is called fine arts, but I fall in love with the possibilities of new technology, my style change an got closer to what would be considered illustrations. You know?i It does’t matter… It makes me happy doing what I am doing…

Judy

22 January

If artists follow the historical perspective that LeVan has presented then no artists would be selling their art. They would simply give it away or store it away. After all anything with a price tag on it is supporting commercialism and all the advertising and marketing dollars that come with it. There is a huge economic sector built on art as this web site illustrates. The only difference is between illustrator and professional artist is that one may have a steadier income, but it may not be the illustrator in some cases.