The artist called himself the most classic of the impressionists. In his works, there is no riot of colors and innovative ideas usual for this direction. The artist studied in Italy using the technique of the masters of the old school, Bellini and Botticelli, and at the age of 18, he became a scribe in the Louvre. Degas had a talent for seizing the moment. He skillfully copied the works of the great, but even better – life itself.

The Nuances of the Artist’s Painting

Imagine the Louvre in Paris in the 1860s: Degas is seated in front of a canvas by the Spanish painter Velázquez, a casual visitor stops and observes with interest in the young artist’s work. The stranger comments on the copy, to Degas’s surprise, with knowledge. A conversation develops between the two men that will grow into a lifelong friendship. The chance visitor turned out to be Édouard Manet, one of the founders of Impressionism, and he brought Edgar Degas into the circle of like-minded people and introduced him to Monet and Renoir.

Degas, like his new acquaintances, sought to move away from the formulaic notion of painting, to turn more to the themes of life and portray it in process, truthfully. His acquaintance with Impressionism did change the artist’s idea of representation, but he was not at all drawn to the landscapes that are so beloved in Impressionist circles. While Monet and Renoir painted from life, Degas stood out from them. He followed the rule “to observe without drawing, and to paint without observing.”

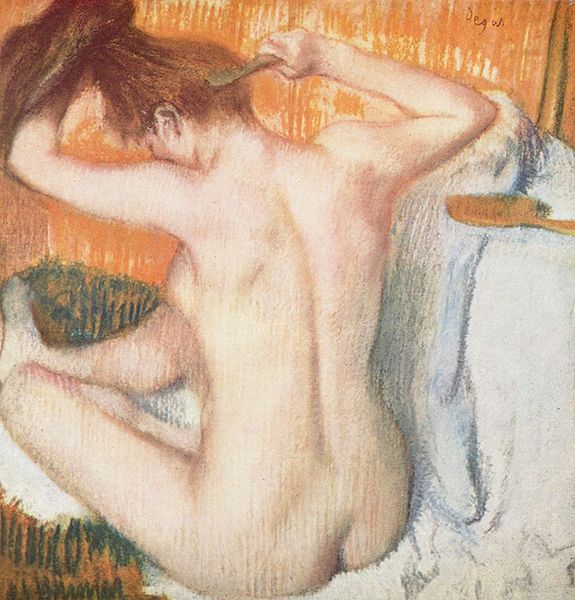

What did Degas mean when he portrayed life as it is? The artist liked to portray people, especially women, and not pose them in a static position. The paintings are as if Degas took them by surprise, as in the 1885 painting Woman Combing Her Hair (Woman at the Toilet). Ballet was another of the artist’s favorite motives. However, he did not paint the bright and graceful figures of dancers but caught them in the dressing room or preparing for a performance. In Rehearsal of the Ballet on Stage, Degas portrayed the dancers in the “run-through” of the performance: the view of the stage falls not from the usual perspective of the stalls, but from the side.

The artist managed to convey the atmosphere of the ballet rehearsal: the “porcelain” silhouettes of dancing girls contrasted with the relaxed figures of ballerinas waiting for their turn. While the Impressionists experimented with color and worshiped light, Degas said, “I am a colorist with lines.”

Success Key Point

Up until the 1870s, the critics ignored Degas. His work was exhibited once, and his work did not bring any income. However, thanks to the means of his family, he was not a pauper. This also distinguished him among the creative elite: not everyone could afford to engage in creative work without being distracted by commercial orders.

The 1870s were a triumph for the artist. After the famous collector Paul Durand-Ruel sold three works by Degas, Edgar reached a new level of motivation and search for himself. He began to create desperately and brightly, finally believing in his own talent. Contemporaries could not even accurately determine the authorship of his works. They seemed to have been created by completely different people — using different styles, techniques, and colors.

Degas attached particular importance to the presentation of his works. He even co-hosted an independent Paris Impressionist exhibition in 1874. This format was characterized by particular freedom, which was not done at the time and was intended to attract the public’s attention to Impressionism. Breaking away from the confines of the Salon, the artists made sure that the exhibition space played to their advantage, a background matching the color scheme was selected for each piece, the artists acted as their own critics and personally selected works for the exhibition. Degas exhibited paintings on his favorite subjects: horse racing, dancers, and washerwomen.

“The idea of the exhibition, already in the air before 1870, was picked up by Claude Monet and supported by Renoir, Pissarro, and Degas. The latter hated the spirit of the Salon and, after Manet retired from business, became the chief organizer of the exhibition. In the eyes of the young artists, Degas became, by right of seniority, the standard-bearer of independent art…” — Art historian Jean-Paul Crespel

However, the Impressionists’ expectations were not met. According to Jean Renoir, the son of the famous artist, “ridicule, insults, and slurs were poured in hail. People went to the exhibition to laugh. The characters of Degas and Cézanne, even Renoir’s charming girls, made people boil with indignation.”

Despite the unsuccessful experience of the exhibition, after the 1880s Degas reached a new level. He was already recognized and people bought his work, but the artist exhibited only in a few places. This halo of mystery attracted collectors and magazines in Paris. Nevertheless, Degas always saw a line between creating work for sale and creating for the sake of art. If we now look at these two types of work, the former seems more refined and classical, while the latter is avant-garde and unconventional.

Later Period

The work of the later period of the artist is characterized by complete immersion in abstraction; the colors became brighter and richer, and the line became clearer and more expressive. In comparison, The Cup of Tea (Breakfast after Bath) depicts one of the artist’s favorite motifs, but already in a completely different palette and contrasts.

During this period, Degas rapidly began to lose his eyesight, and to observe all the proportions of the girls, he made strips of markings directly on the bodies of sitters. In his last works, the artist created almost blindly. Experts say that Degas, like Monet, had progressed macular degeneration for 20 years, and because of this, these Impressionists saw their paintings differently than ordinary viewers. Using computer simulations, researchers recreated the paintings through the eyes of the artists. The result was blurry images in dim tones with barely discernible silhouettes.

After 1912, the artist was forced to leave his studio apartment. Degas seemed to completely abandon creativity and was seen wandering the streets of Paris, almost completely blind and deaf. Occasionally he would stop by at old auctions and art exhibitions, with faithfulness to art for the rest of his life.

___________________________

About the Author:

Jean S. Hartley is a content writer in an online paper writing service, that provides quality assistance for students. Jean also enjoys local folklore and customs. She is going to blog about it on YouTube.

NO COMMENT