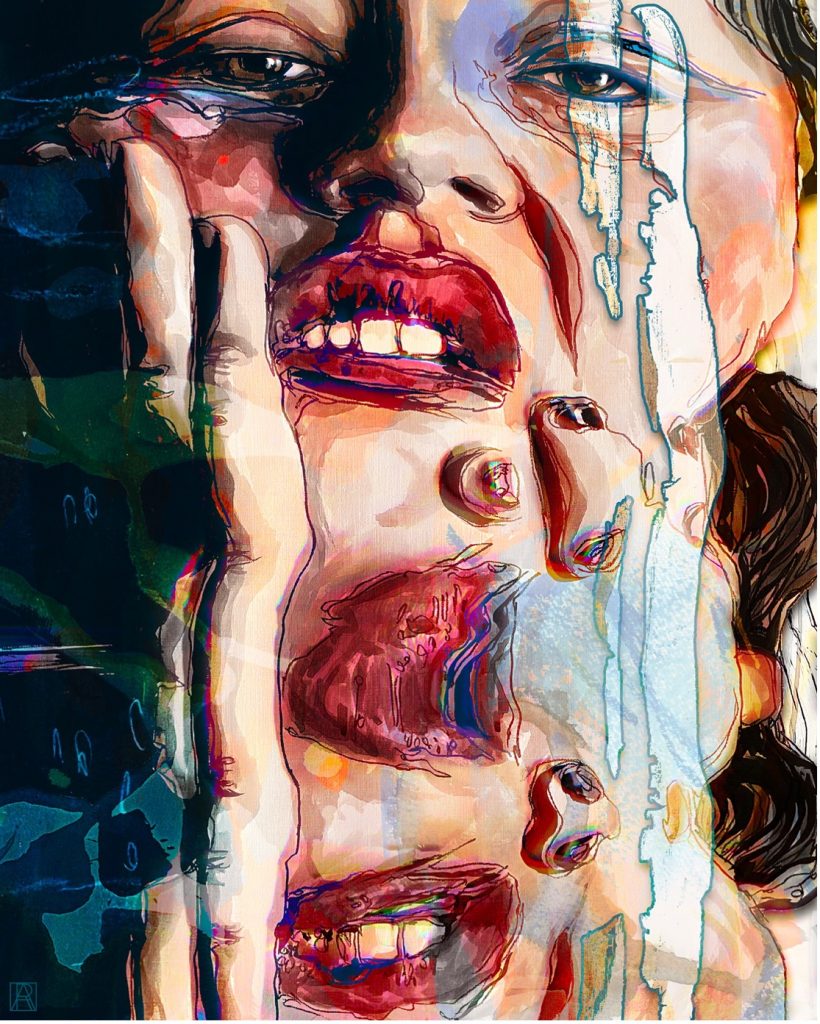

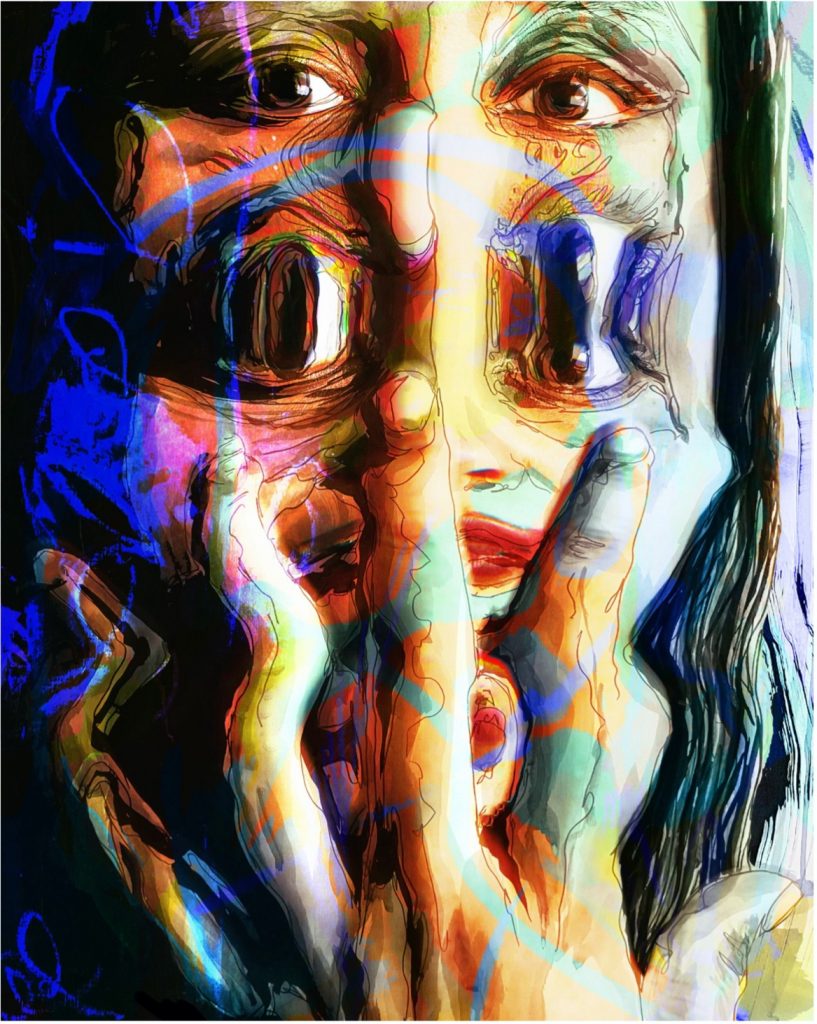

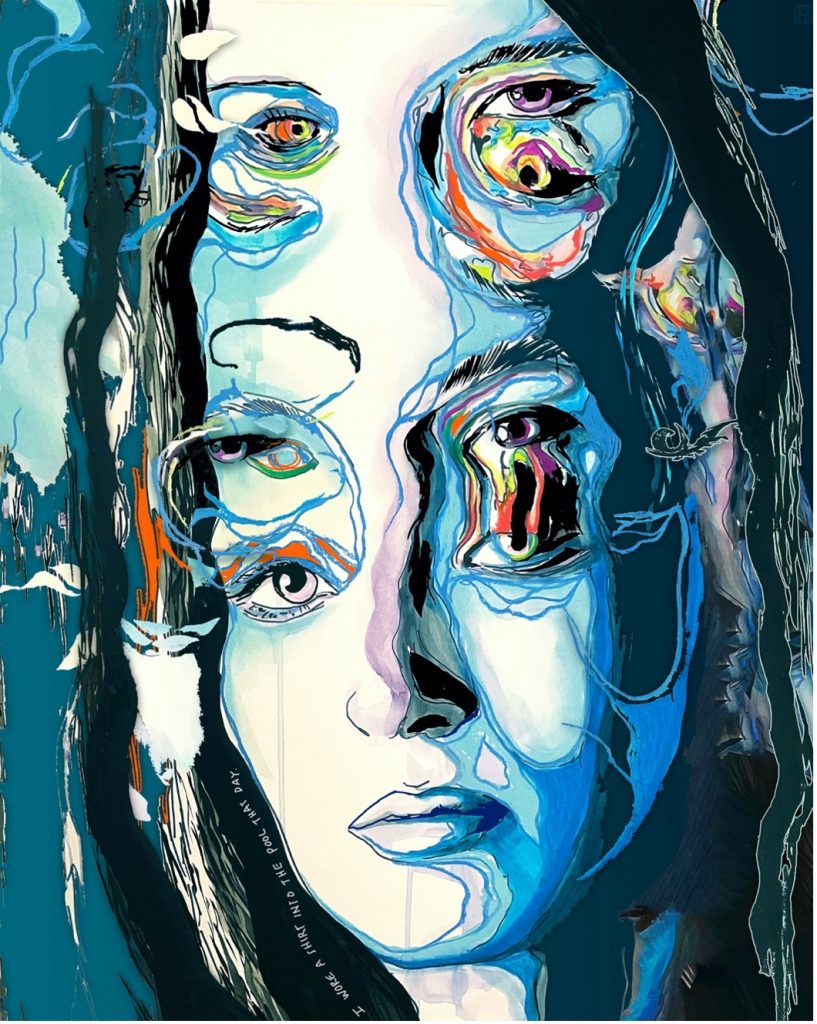

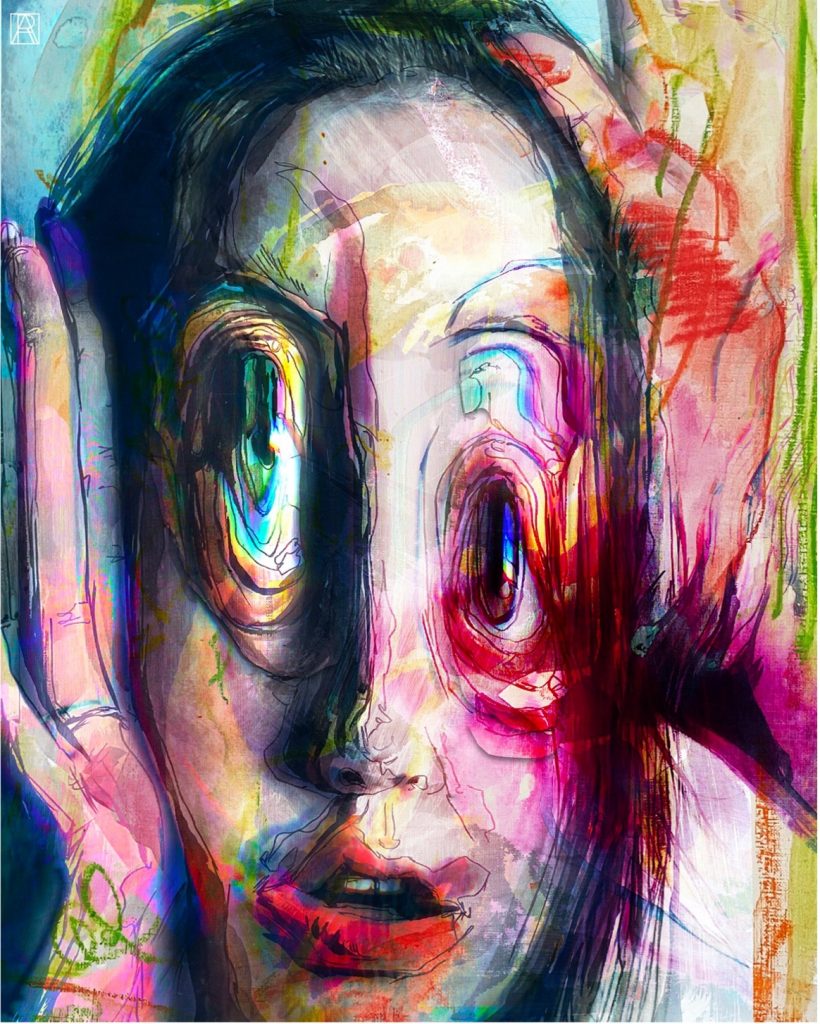

Dysmorphic III comments on the psychic complexities of having Body Dysmorphic Disorder. BDD is a mental health disorder in which sufferers fixate on one or more perceived defects or flaws in their appearance — a flaw that appears minor or cannot be seen by others. This preoccupation with an “imagined” defect often leads to isolation and the avoidance of social contact. This perceived flaw and repetitive behavior causes distress and significantly impacts one’s ability to function in daily life. This series attempts to illuminate the experience of a warped sense of reality through the synthesis of expressionistic portraiture and anecdotal commentary. The work focuses on stylistically representing the psychological state of dysmorphic thought and the significant impact it has on visual reality testing. Dysmorphic III emphasizes the existential importance of real vs. perceived observations.

Having deep personal experience with the uncomfortable complexities of BDD, my work addressing eating disorders raises questions about the issues that culminate at the intersection of femininity and patriarchal social constructs. Living in the age of technology has quite literally and figuratively warped our minds into thinking our natural state is a glitch, something to be fixed or remedied to be accepted. Dysmorphic III highlights the very real threat that our current society poses.

For the third iteration of my Dysmorphic series, I felt it prudent to elevate the stories of other women who experience the disorder. In doing so, I was able to gather six women, other than myself, to attend a reference photoshoot at my studio as well as a small, but intimate interview. During these four hours, the women could openly discuss and relate to one another. While many of these women have participated in group treatment or therapy, the focus on support and positivity in my studio left an indelible mark. We all began to comprehend that the distortion we perceive is not based in reality, but actually, in the post-photo warping and image treatment work I conducted in the studio. It’s not often that a group of women suffering from the same disorder come together to create, understand, and grow from such experiences, however, these bold and confident women enabled a deeper understanding of BDD not only for themselves but for my own artwork and the resulting portraits reflecting dysmorphic thought.

The etiology of BDD appears to develop from biological, cultural, psychosocial, and neuropsychological factors. Presently, it affects between 1.7 and 2.4 percent of the population or approximately 1 in every 50 people. In the United States alone, it is believed that between 5 million and 7.5 million individuals suffer from Body Dysmorphic Disorder. While the prevalence of BDD is pervasive in our culture, the awareness and functions around the disorder are widely misunderstood, analyzed, and seldom discussed in mainstream discourse about mental health. While BDD is experienced by both men and women, women tend to grapple with the condition at higher rates. This discrepancy may be due to additional societal pressures placed on the importance of female appearance. “Women are expected to have small waists, flat stomachs, big breasts, a round ass, an angular face and jawline, smooth skin… It’s impossible,” stated Alex L. one of the women portrayed in this series. The immense pressure of functioning in a society where idealized physical perfection is valued above all else, where beauty products and “quick fixes” are pushed down our throats, and where intrinsic value for women is based on pleasing others leads to an internal breakdown of confidence, self-acceptance, and worth.

We live in a society where physical perfection is the silver bullet for happiness. Influencers promoting and profiting off “flat tummy teas,” taking weight loss drugs to fit into clothing, and editing their appearances to promote unrealistic beauty standards set an example for young women that worth is derived from one’s appearance. Rampant increases in depression, anxiety, BDD, and eating disorders, in general, are the result. Is this reality, or is this a pill being fed to us by those that wish to control, subdue, exploit, and profit off of women’s insecurities? By exploring the correlation between psychological states and the expression of the human form, I attempt to peer into the moment where societal pressure and psychology meet, where expectation and acceptance clash, and where reality and non-reality diverge.

For much of my life, I have struggled with dysmorphia and disordered eating. Commonly, those who struggle with BDD invariably deal with feelings of shame, guilt, or loneliness. In an effort to better understand others’ experiences with BDD, I decided to paint women who themselves experience this disorder. When interviewed, these women’s stories paralleled each other dramatically. “I wished my cheeks were smaller and that my face was more angular. I thought the dark circles under my eyes made me look sullen and exhausted and my pale skin made me look sick. I felt like every part of my body needed a tweak and it was exhausting trying to exist in public.” stated Alex L. “I still feel worthless most of the time because of what I think I look like,” said Supriya D. The women pictured in this series exemplify the immense pressure placed on one’s appearance in an effort to feel valid, worthy and accepted by a society fueled by thinness and conformity.

Personally, it often feels as though my outward appearance and internal dialogue are two separate people. I feel that the shame I carry with me on a daily basis due to my disorder infiltrates every aspect of my life, except my artwork. The studio is essentially the only place I feel the impact of my ED and BDD fall by the wayside. In college, as my ED raged, I was faced with a choice: Was my eating disorder going to “consume” my creative spirit, or would my artwork help to heal constant critical voices in my head? I knew all too well that these two aspects of myself were either going to destroy each other or come together to heal one another. I am still on that journey.

In an attempt to translate my own thoughts and feelings to the canvas through previous iterations of the Dysmorphic series, I found that making the invisible visible was an invaluable tool to help better comprehend my disorder. Being able to do this for me was not only a learning tool but also served as a connection to others with similar issues. Dysmorphic III shifts focus from my experience to that of others with similar struggles. In doing so, all my subjects, including myself, began to question the inherent loneliness of the disorder. We were in fact, not alone. Additionally, seeing themselves as an artistic representation of BDD allowed my subjects to better understand the warped nature of their reality. These portraits helped the women to separate from their perceived versions of themselves and question the pejorative nature of their internal dialogue. I attribute this shift to the aesthetic force of art.

The ineffable qualities of consuming art are transcendent. Art allows the viewer to sit in introspection and to question oneself, no matter the discomfort level. I believe the same to be true in unlearning the deeply toxic functions of diet culture. We must confront to overcome, and we must reflect in order to progress. Art allows us to tap into the recesses of our minds to expose the complexes at the core of our psyches. By confronting such deep-rooted issues, one can begin to lift the societal veil and start comprehending the capitalist, racist, and misogynistic functions of Western beauty standards that we so easily accept as “truth.”

We, as citizens of the modern era, are constantly barraged with images of perfected, altered, unachievable bodies. The impact of such imagery has become deeply rooted in the fabric of our self-identification. We use terms such as “bikini body” and “summer body” to emphasize the importance of thinness and its impact on broad societal acceptance. These overtones only shame those with real or perceived non-conforming bodies and make them feel unworthy of praise, love, and self-confidence.

The purpose of art is to challenge the viewer and question accepted notions of reality, paralleling the nuanced intricacies of treating BDD. In creating Dysmorphic III, I focused on providing not only a bridge of connection between those who experience the disorder themselves but also the greater public. BDD is not a rare occurrence these days. As our culture began to intertwine heavily with consumerism, celebrity, and technology, people have come to suffer from disorders such as BDD at increased and alarming rates. This unfortunate truth should urge people to question the purpose of societal standards and the functions in which they work to elevate conformity and repress individuality.

Who benefits from a homogenized culture? Who benefits from women being preoccupied with their looks? Who benefits from a culture focused more on appearances than the sociological happenings of our time? How would a distracted constituency enable those in power to resume activities that further oppress women? Dysmorphic III serves to exemplify the very real impact our current society has on women who participate, digest and embody the values of our culture, distortion and all.

______________________________________

Alex Rudin is an NYC-based multimedia artist & illustrator focused on social justice and abstract political theory. In 2019 she founded her creative studio Rudin Studios, LLC. Alex’s artwork is narratively focused with a strong emphasis on expressive portraiture. Much of her work attempts to comment on the complexities of the human experience through stylized portraiture and anecdotal commentary. Alex’s focus lies in uncovering and expressing the truths of what it is like to live in modern America. She is currently focused on creating work to galvanize action around social and political issues. This year Alex has partnered with organizations such as Women for Biden Harris 2020, Women for the Win, Women Rising, Women’s Rights Information Center, and Her Bold Move among numerous other female-led socio-political orgs in addition to working in the human rights space with organizations such as Article 3, The Representation Project and the Sam & Devorah Foundation for Trans youth. Rudin’s work has been featured in publications such as Art Daily, Authority Magazine, Yahoo!, and USA Today, to name a few. Alex’s fine artwork has been shown in both solo and group exhibitions in New York City, Great Neck, Delaware, Philadelphia, and the Hamptons. Alex recently debuted the inaugural 32-piece exhibition of The Age of Empathy at Jersey City, City Hall. The Age of Empathy is slated to start touring in 2022.

For more of Alex Rudin’s work, please visit her Instagram @_alexrudin, her website www.alexrudin.com, or her online store www.rudinstudios.com.Set featured image