In the beginning…

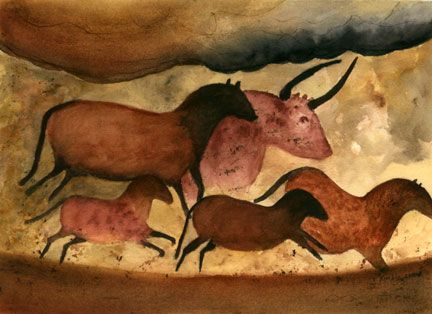

The history of art is as old as the history of humans on Earth. Art developed when prehistoric people started drawing on the cave walls for different reasons. It started in the stone age when our ancestors learned how to make different objects like arrows and bowls out of stone first. After that, it took off.

The word “art” is derived from the Latin ars, which originally meant “skill” or “craft.” These meanings are still primary in other English words such as “artifact” and “artisan.” The meanings of “art” and “artist,” however, are not so straightforward. We understand art as involving more than just skilled craftsmanship.

When asked this question, students typically come up with several ideas. Much art is visually striking, and in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, the analysis of aesthetic qualities was indeed central in art history. During this time, art that imitated ancient Greek and Roman art was considered to embody a timeless perfection. Art historians focused on the so-called fine arts—painting, sculpture, and architecture—analyzing the virtues of their forms. Over the past century and a half, however, both art and art history have evolved. With time and space, and even new ideas.

The world of art is dedicated to serving the intellectual, spiritual, and social demands of an individual and a diverse community. It is an early microcosm of the early modern art world we now live in. At times it seemed like a club ruled by institutions and high-powered individuals, collectors, consultants, and board leaders that ultimately defined what is important.

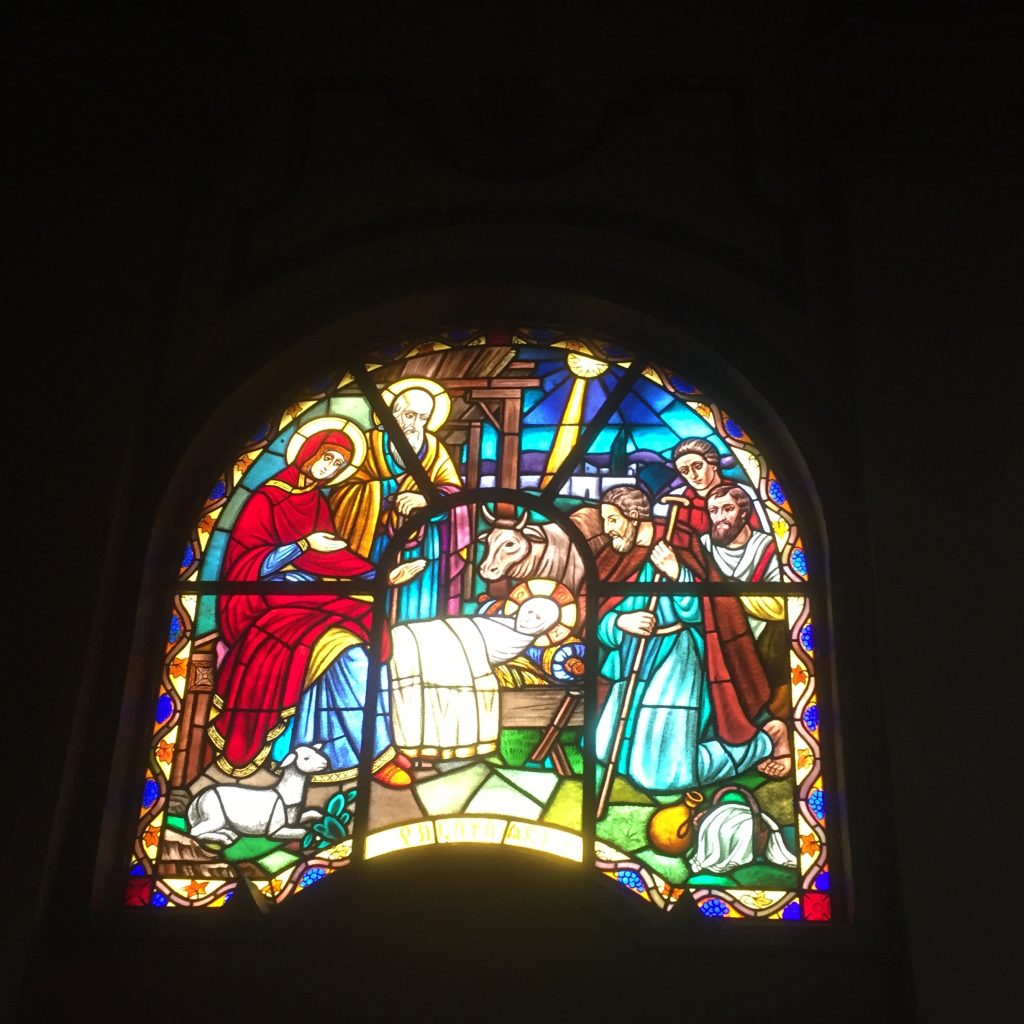

Art emphasized originality, creativity, and imagination. This reflects a modern understanding of art as a manifestation of ingenuity of the artist. This idea, however, originated five hundred years ago in Renaissance Europe and is not directly applicable to many of the works studied by art historians. In the case of ancient Egyptian art of Byzantine icons, the preservation of tradition was more valued than innovation. While the idea of ingenuity is certainly important in the history of art, it is not a universal attribute of the works studied by art historians.

All this might lead one to conclude that definitions of art are subjective and unstable. One solution is to propose that art is distinguished primarily by its visual agency, that is, by its ability to captivate viewers. Artifacts may be interesting, but art has the potential to move us — emotionally, intellectually, or otherwise. It may do this through its visual characteristics, expression of ideas, craftsmanship, ingenuity, rarity, or some combination of these or other qualities. How art engages varies, but in some manner, art takes us beyond the everyday and ordinary experience. The greatest examples attest to the extremes of human ambition, skill, imagination, perception, and feeling. As such, art prompts us to reflect on fundamental aspects of what it is to be human. Any artifact, as a product of human skill, might provide insight into the human condition. But art, in moving beyond the commonplace, has the potential to do so in more profound ways. Art, then, is perhaps best understood as a special class of artifacts, exceptional in its ability to make us think and feel through visual experience.

Thinking back, we are all born with tastes and preferences. Art appreciators know that those opinions make art fun! One of art’s goals is to create conversations that share perspectives and cultures across borders. It helps us share the world through collective eyes. The truth is that artists, and the art they create, lie on a path that they created and follow.

Visual art is as diverse as music in its offerings, but artists and insiders are the only ones that see that. A cultural redefinition and demystification of art is necessary to truly recognize art’s true potential in modern culture.

For us, art history books remain a viable source of information. We search for specific artists who find one that does have a color, come from a different region of the world, or even have an art history outside the region. Topic-based books might be more inclusive, but they focus on a single subject. To understand how their particular artist or movement connects to others is a herculean task we might want to face and understand.

In fact, ultimately, art is basically how we share our experiences with the world. Art is a range of activities people do to express their thoughts, ideas, and emotions. It is a way to portrait the concepts that can’t be expressed by words, that aim to create powerful emotional connections between several cultures with different values.

Technology is providing more opportunities than ever before for artists to get their names out there. Visual art learning is reliant on a complex system of perceptual, higher cognitive, and motor functions, thus suggesting a shared neural substrate and strong potential for cross-cognitive transfer in learning and creativity. From prehistoric times, visual art has been a form of communication deeply imprinted in human nature; the act of experiencing art and esthetic appreciation in the “receiver” also has the power of cross-cognitive effect any time during individual development.

The ability to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty during the creative process is an important mental trait. The tolerance for ambiguity is also an important attribute in learning in order to deal with the complexities and ambiguities of knowledge.

All too often, the arts are marginalized in our schools. In response to this marginalization, educators have sought to justify the arts in terms of their instrumental value in promoting thinking in non-arts subjects considered more important, such as reading or math. There has been little convincing research that the study of the arts promotes academic performance. Art classrooms might be choosing the visual arts as their point of departure.

And that departure can be from the past to the future.

Evidence shows that in the first period of recording history, art appeared through the first official written language. In the civilizations of Mesopotamia language was based on how clay tablets are used to record alphabets. People developed their special writing language on papyrus papers. Civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia created their enormous art with bold artworks such as Ziggurats and the Great Pyramids.

Romans and Greeks created another aspect of art when they started drawing human models while other artists used nature subjects as their art models.

Modern art was with the Art of Antiquity published by Winckelmann in 1764. Modern art slowly began to gain traction in the late 18th century and rose in popularity in the late 19th century.

From then until now, art continues to evolve by the day and found new meanings every time. In the 21st century, art is not just limited to drawings and sculptures. Everything from photography to an electronic product can have art infused into it.

In fact, a hundred years ago, consumer market research was a massive undertaking. Today, it couldn’t be easier. Thanks to the hard work of market research pioneers like those profiled above, modern solutions like Attest are able to combine all the learnings of the last 10 decades.

Market research no longer has to be a long and costly process carried out by academics. These new tools mean any person, in any brand, can ask their target customers questions and get actionable insights in the space of a few clicks.

Whether it is street art, sculpture, drawings, pop art, contemporary, realistic, abstract, maximum, or minimum, art today is the same as before. But with learning and understanding developed, new ideas and references to the time we first learned about art and what we might use.

Today, art is art. It is what we can use. It is what we can enjoy. It is what we learn. It is what will make us the new artist we want to see and become. The art industry is an ever-changing industry filled with vision, beauty, and purpose in its highest form. It is in constant change and evolution and we see better creation as we progress.

____________________________

About the author:

Ron Rossi is an international writer, editor, as well as an art consultant with extensive experience writing articles on art and history, as well as working with collectors, galleries, museums, and art foundations. He has traveled the world and is writing a book on living in China managing an art gallery.