François Chartier takes a theatrical approach to photorealism.

by Julie Jacobs

For 25 years, François Chartier toiled as an art director and illustrator in magazine publishing and advertising, working for such well-established Canadian agencies as Vickers & Benson (now Arnold Worldwide Canada) and creating the visual concept for Cirque du Soleil’s “Quidam” and “O” in Las Vegas. He even ran his own studio for a brief period with a designer friend and was a forerunner in offering Photoshop services. But when he turned 50, he decided to change course and took up painting full time. Today, Chartier is among the most renowned and revered artists of photorealism.

For 25 years, François Chartier toiled as an art director and illustrator in magazine publishing and advertising, working for such well-established Canadian agencies as Vickers & Benson (now Arnold Worldwide Canada) and creating the visual concept for Cirque du Soleil’s “Quidam” and “O” in Las Vegas. He even ran his own studio for a brief period with a designer friend and was a forerunner in offering Photoshop services. But when he turned 50, he decided to change course and took up painting full time. Today, Chartier is among the most renowned and revered artists of photorealism.

“By the time I was 40, I found that advertising had changed and was more of a game. It had given me a lot, but it wasn’t [doing so] anymore, so I looked into painting. It was the only logical direction, as my experience, personal taste, longings and training had prepared me for this path,” says Chartier from his Montreal studio.

Chartier wound up detouring and doing Photoshop for many years, soon becoming financially secure enough to just paint. “The idea of having the freedom to do my own thing my own way, workwise, greatly appealed to me. For a long time, it was work, work, work, almost 24/7.”

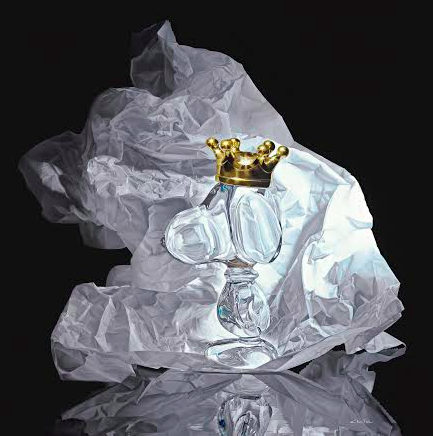

Typically painting Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Chartier doesn’t put in nearly as many hours as he once did, but his dedication to craft remains steadfast. He spends three to four months on each painting, with a unique attention that creates, “through layering of mediums and the play of the brush, the illusion of depth and [the] sense of presence beyond what is found in photographs.” Such photorealistic quality is evident in all his series, which include Wet Paint, Waterworld, Simply Flowers, Pop Culture Icons and Paper Beauties. His vision is particularly original in the last of these series, Paper Beauties. For this collection, he drapes crumpled tissue paper around a still- life object for an interesting juxtaposition.

“I look at my work as ‘new realism’ rather than photorealism. I’m not trying to be so precise. Very often, the photorealistic artist gets too stuck in the details, (so) that the painting looks too clean, too perfect. I’m trying to get as much mood as I can into my paintings,” explains Chartier, who is always acutely aware of his audience. “All I want is to paint something that people will find beautiful. I would have no pleasure in it if nobody responded to it.”

He need not worry. His work has shown in galleries and collections throughout Canada, the United States, Europe and Mexico, affording him the opportunity to meet with fans, which he finds exciting and says motivates him to paint more. He currently is represented in Montreal, at the Plus One Gallery in London, and at the Royal Gallery in Providence, R.I.

Preparation and Process

Chartier describes his approach to photorealism as theatrical. He first must find the right object or objects with which to build a set. He then extensively photographs these objects to ultimately achieve the right composition and lighting. For each painting, he takes hundreds, even thousands, of photos and later uses his Photoshop skills to correct and, in some cases, combine the images. He works from both the selected images and the still life itself.

“Photorealism is very organized and planned, rather than intuitive. I spend a lot of time preparing my photos, more so than for the actual [oil] painting. With the tissue paper, it can be especially challenging, which is why I take so many pictures,” says Chartier, who enlarges the final image for tracing. “But I also like to keep the object around. It can be tricky. … I wonder why a line is not straight in the photo, and I can look at the object and see why.”

He works on big canvases to render his subjects larger than life size. A recent one measures 5 by 5 feet. His goal is “to capture viewers and make them look at something they know but at a different angle with the smaller details revealed in their beauty and simplicity.” Before painting, he coats the canvas with a gesso base to mute any signs of texture and brush stroke. Weeks later, he adds the finishing touches and varnish.

Light-Bulb Moment

Raised in Montreal, Chartier was always interested in the visual arts. He developed his acumen not in art school but on the job, during which he also learned about typesetting, photography and color separation. His first encounter with an airbrush was during a stint at a sign company.

A date with friends inspired his eventual focus on photorealism. He had been visiting New York City and strolling in the East Village after a night of disco dancing. Walking past a gallery on Prince Street, Chartier noticed a painting in the window: “Gumball Machine” by Charles Bell.

“I told myself, ‘One day I’m going to do something like that,’” he says. “That painting changed my life.”

And life is good these days. Chartier has both realized his dream and taken more time for living, enjoying his home, his travels and such pastimes as archery and scuba diving. Still, he admits with a laugh, “Every Monday, I’m very anxious to get back to my studio and my paintings.”

For more about François Chartier, visit francoisc.com

1 Comments

Wonderful paintings! I love the amaryllis.