Find out what art critics are looking for in a gallery exhibition.

by Melissa Hart

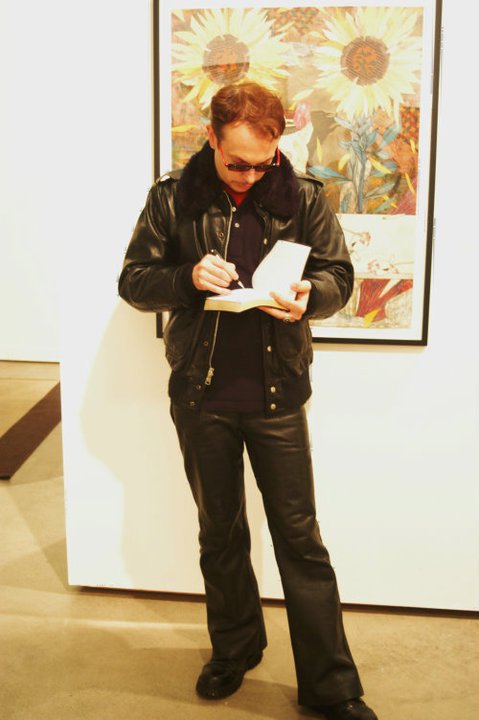

Richard Speer doesn’t spook easily. As art critic for Willamette Week, Portland’s highly regarded alternative weekly newspaper, Speer has strolled through galleries in and around the Oregon city for more than a decade. He’s seen unsettling creative work, including William Pope.L’s giant reverse image of the United States made out of 5,000 rotting hot dogs. He’s also seen an upscale-gallery show featuring the paintings of Rama—a 21-year-old Asian elephant at the Oregon Zoo. Still, when Speer walked into Breeze Block Art Gallery in Portland’s Chinatown arts district last March, he felt as if he’d entered a haunted house … albeit one from someone’s bland, colorless childhood.

“It was an installation that took up the entire gallery,” Speer recounts. “[The artist] painstakingly created a stylized minimalist interior of a typical suburban house. … There was this very eerie soundtrack of ambient noise going on, and, for me, it captured the sinister underbelly of the American suburban dream. I really liked it.”

As an art critic, Speer approaches gallery exhibitions in two ways. He often studies press releases, images and artist statements before a show opens, and he suggests that gallery owners get promotional materials, including high-quality photos, to arts writers at least two weeks before a show. Sometimes, however, he simply wanders into a gallery from the street. “I try to go into every show as a tabula rasa and let it have its way with me,” Speer says.

He believes a show should be visually strong on its own; the viewer shouldn’t have to rely on an artist’s statement and press release to make it meaningful. “Certainly, it helps to be able to learn more about it and to talk with the artist, but I’m more interested in what the show does visually,” he says. “Does it knock your socks off if you don’t know anything about it beforehand? To me, that’s an important consideration.”

A positive review of a gallery show inspires increased attendance and sales. A scathing assessment of the sort Speer sometimes feels moved to write may shake the confidence of those involved in an exhibition. Even a negative critique, however, offers opportunities to learn from critics who devote their lives to studying and writing about art.

Farther south on the West Coast, critic Kenneth Baker has spent 28 years reviewing art for The San Francisco Chronicle. He describes himself as even-tempered and notes that a less-than-glowing review can draw attention to someone’s art that it might not otherwise receive. This is especially true if “it’s written by someone like myself, who doesn’t say much negative about someone’s work. Interest arises,” he says. “People wonder what got up my nose about this work in particular.”

Baker prefers to go into a gallery with little research beforehand “because I like to confront the show,” he says. “I’ve had enough experience now that I bring a great deal of general knowledge of the major artists of our time, and many of them I’ve written about before.” He’s interested in examining the exchange between artist and viewer; his reviews provide readers with the intellectual and historical context that informs both the artist and the work.

In a recent analysis of paintings by Hung Liu, Baker delves into the Oakland artist’s childhood in China. The critique provides readers with details about the rich political historical era of Liu’s childhood, during which Mao’s Cultural Revolution heavily influenced the future artist. Baker intertwines these details with his own observations on the work as it appeared in two related exhibitions last March.

Like Speer, Baker writes with a palpable enthusiasm for art. “I’m one of the last resident art critics around,” he says. “The amount of art activity in this town is so great that it’s a real priority. … It can’t be ignored.” After almost three decades as a critic, he still speaks of gallery shows as extraordinary offerings.

“Things are cleared out of the way for concentration and focus,” he says of rooms devoted to painting, sculpture and the like. “We can spend as much time as we please without having to pay for it. We encounter so few public situations where that’s the case.”

He prefers to see a manageable amount of material in a gallery show. “Don’t overwhelm people,” he says. “Too much information insults your experience. The right information, even if it’s information you don’t enjoy, is more memorable. You might find it memorably hateful, but, nevertheless, you do remember it.”

Speers agrees that a compelling show “allows the artwork plenty of room to breathe.” He looks for a space conducive to physically leading the viewer through a room. “I like galleries that have a mixture of natural and gallery lighting,” he says. “It’s nice to see work in different moods of sunlight.”

Baker notes that the order in which a gallery presents the pieces can be vital, particularly in an installation show in which video work appears along soundless work. The juxtaposition sometimes presents problems. “ I understand that this is difficult,” he says. “Sound installation is expensive. Nonetheless, I find it annoying to hear someone else’s work when I’m trying to focus on another piece.”

He suggests that newer gallery owners pay close attention to what feels right in other galleries. “Look at who’s succeeding and how they’ve done it,” he says.

Speer emphasizes the importance of establishing a strong aesthetic for a gallery. “Have a curatorial point of view and keep the quality control consistent from month to month,” he says. “I’ll know going into the show. … Whoever the artist is and whether I wind up liking [the] work or not, the show will be, at the very least, an intriguing body of work.”

He also gravitates toward a consistent thesis, especially when it informs an entire show.

Pacific Northwest artist TJ Norris curated “Off the Plain,” an exhibition that appeared in Portland’s Place Gallery this spring. “It did a really marvelous job of stating its thesis—in this case, the idea that photography can be a medium used in sculpture,” Speer says. He describes origami-like photo sculptures and round photos in record sleeves, with one atop a 45–rpm turntable. “I thought that show carried out its purpose in really inventive ways,” Speer says.

Speer concludes with the words every gallery owner longs to hear: “That was a show I was thrilled about,” he says.

Melissa Hart teaches at the School of Journalism and Communication, University of Oregon. Her writing has appeared in numerous periodicals including The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Hemispheres and High Country News.

1 Comments

memorably hateful, but, nevertheless, you do remember it. Thats a great line.

go into a gallery with little research beforehand “because I like to confront the show,. Thats interesting too.